The A01 Corpus

A Digital Gateway to 80 Classical Commentaries, the Qurʾan, and Persian Hypertexts

The A01 Tafsir Corpus brings together one of the most extensive curated digital collections of Qurʾanic exegesis available today. It comprises:

- 80 Arabic Tafsir works digitized and originally published by the Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute on Altafsir.com,

- the Qurʾan in TEI-XML (Corpus Coranicum), and

- Jalal al-Din Rumi’s Persian Masnavi, also in TEI-XML.

All texts are accessible through the A01 Tafsir Web Application (the protoype is available via this link), which supports rapid search, TEI-aware navigation, annotation, and AI functions, such as similarity filtering based on document embeddings.

Tafsir as Genre: Diversity and Structural Coherence

Tafsir is historically diverse, ranging from transmitted, linguistic, theological, juridical, and Sufi approaches to varied authorial styles (for Tafsir as a genre, see Sinai 2009; Görke and Pink 2014; Pink 2010; Pink 2011; for its history and doctrinal diversification, see Gilliot; Rippin; Shah and Abdelhaleem 2020). Despite this variety, classical Tafsir maintains a shared metatextual architecture: a verse-by-verse exposition anchored to the same Qurʾanic hypotext.

This structure makes Tafsir exceptionally well suited to comparative and diachronic analysis. Because all commentaries respond to the same sequence of verses, researchers can trace how metaphors, doctrinal positions, and interpretive strategies develop across centuries, regions, and intellectual traditions.

To strengthen this diachronic perspective, our approach follows the chronological ordering of the Qurʾan proposed by Sinai (2009) and Neuwirth (2010), based on Nöldeke (1909) and applied in the Corpus Coranicum project (Corpuscoranicum.de, 2007–2024). Integrating this chronology allows us to map the development of key metaphors—such as the ṣirāṭ (“straight and solid road”)—across the Qurʾan and Tafsir, tracing their evolution within and beyond the Arabic exegetical tradition (Seidel & Büssow 2025a).

Methodological Grounding

The A01 corpus is designed to support a combined philological, metaphor-analytic, and digital-humanities methodology:

- Transtextual Theory: Our analysis is grounded in the concept of transtextuality as defined by Gérard Genette—a taxonomy of textual relations (intertextuality; paratextuality; metatextuality; architextuality; hypertextuality) that helps us understand how Tafsir works relate to their hypotext (the Qurʾan) and to one another. We apply this framework in a novel way to the Qurʾan–Tafsir constellation: treating the Qurʾan as the hypotext, and Tafsir works as metatexts / hypertexts commenting upon and transforming that hypotext. (For theoretical discussion of this application see Seidel, forthcoming.)

- Metaphor Annotation: Using the CRC 1475 Annotation Guideline and the Metaphor Papers framework, we mark lead metaphors, explicative metaphors, and their interpretive trajectories (including the ṣirāṭ metaphor explored in Seidel & Büssow 2025b).

- Digital Corpus Methods: The A01 Tafsir Web Application allows verse-aligned comparison across dozens of works, TEI-based linking between Qurʾan, Tafsir, and Persian texts, and automated parsing for quantitative exploration.

Corpus Scope, Biases & Our Extensions

The 80 Arabic Tafsirs form a substantial, but inevitably selective, cross-section of the historical tradition. As Ross and others emphasize, the majority of known Tafsir works remain unedited or undigitized; non-Arabic traditions (Persian, Ottoman Turkish, Urdu, Malay) and several interpretive currents (Sufi, Shiʿi, modernist, women scholars) are still underrepresented.

To address part of this imbalance, the A01 corpus includes Persian material and Qurʾan-related hypertexts, and is designed to be expanded with further non-Arabic and second-degree hypotexts.

The Masnavi — Extending the Transtextual Scope

Rūmī’s Masnavi enriches the corpus in three key ways:

- Filling the Non-Arabic Gap: Persian exegetical engagement with the Qurʾan constitutes a major interpretive tradition. Including the Masnavi provides access to a Persian discursive world, especially valuable for studying metaphors of “way,” “path,” and guidance central to the A01 project.

- Capturing Hypertextual and Metatextual Relationships: The Masnavi is not a Tafsir—a metatextual commentary—in the classical sense, yet it functions as a hypertextual commentary. Rūmī presents it as an “unveiler of the Qurʾan”, and it sparked its own chain of commentaries—making it simultaneously a Qurʾanic hypertext and a second-degree hypotext.

- Preparing for Future Corpus Growth: The project aims to expand the corpus with additional Persian Tafsirs and other second-degree hypotexts, such as the Persian Bayān, thereby enabling large-scale, multilingual, and multi-layered transtextual research.

Since the corpus combines the structural consistency of classical Tafsir with additional Persian hypertexts, it is ideally suited for both close hermeneutical reading and distant reading digital analysis.

Some Characteristics of the 80 Arabic Tafsir Works

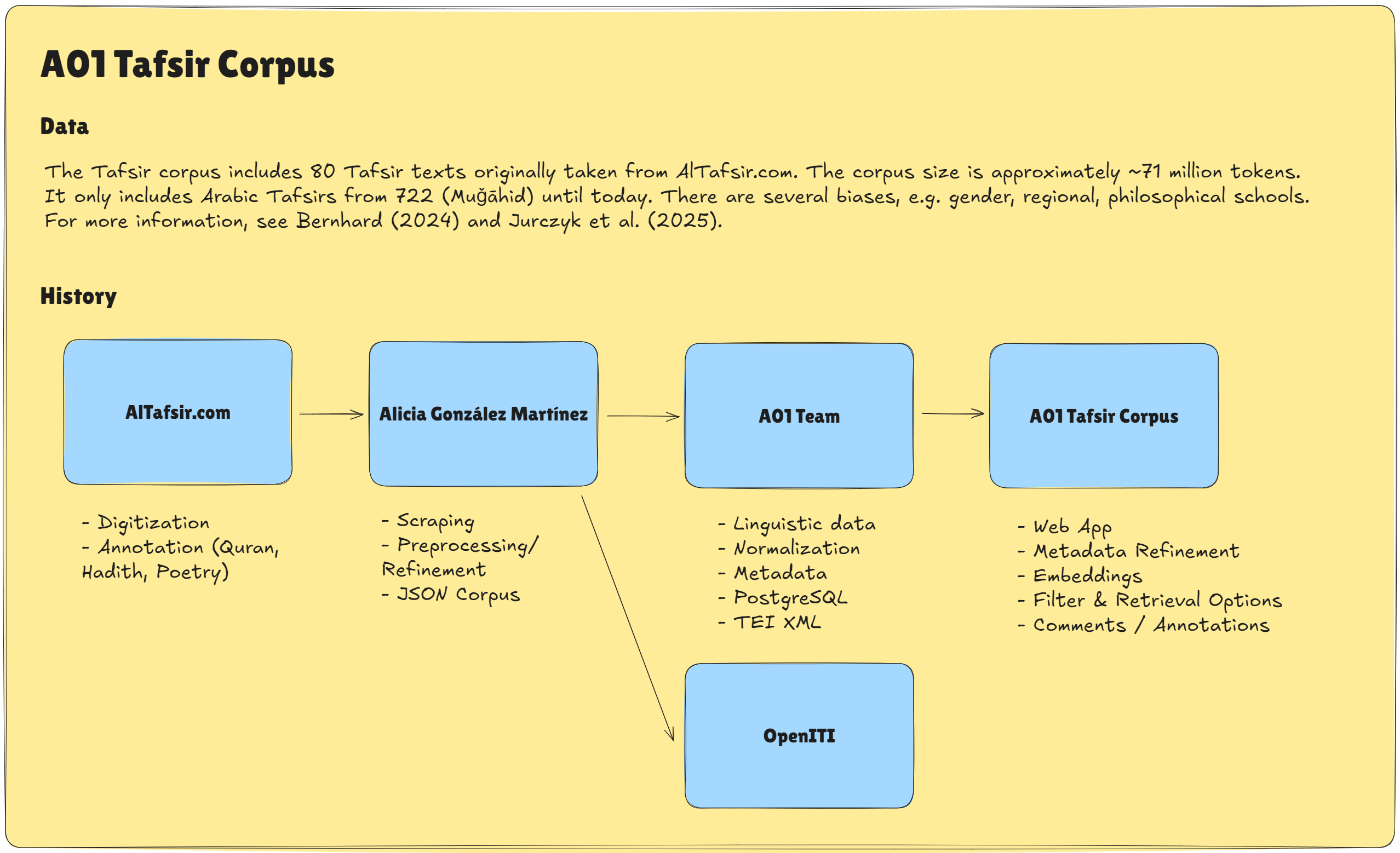

The 80 Arabic Tafsir works, constituting the major part of our corpus so far, were first scraped by Dr. Martínez González, refined, and compiled into a JSON corpus (Martínez 2016), which was later integrated into the larger OpenITI corpus (Nigst et al. 2023). This JSON corpus was subsequently processed and enriched with linguistic information by Adrian Bernhard in his master’s thesis (Bernhard 2024). It also includes metadata provided by the A01 project team, which maintaines, refines, and continuously expandes the corpus.

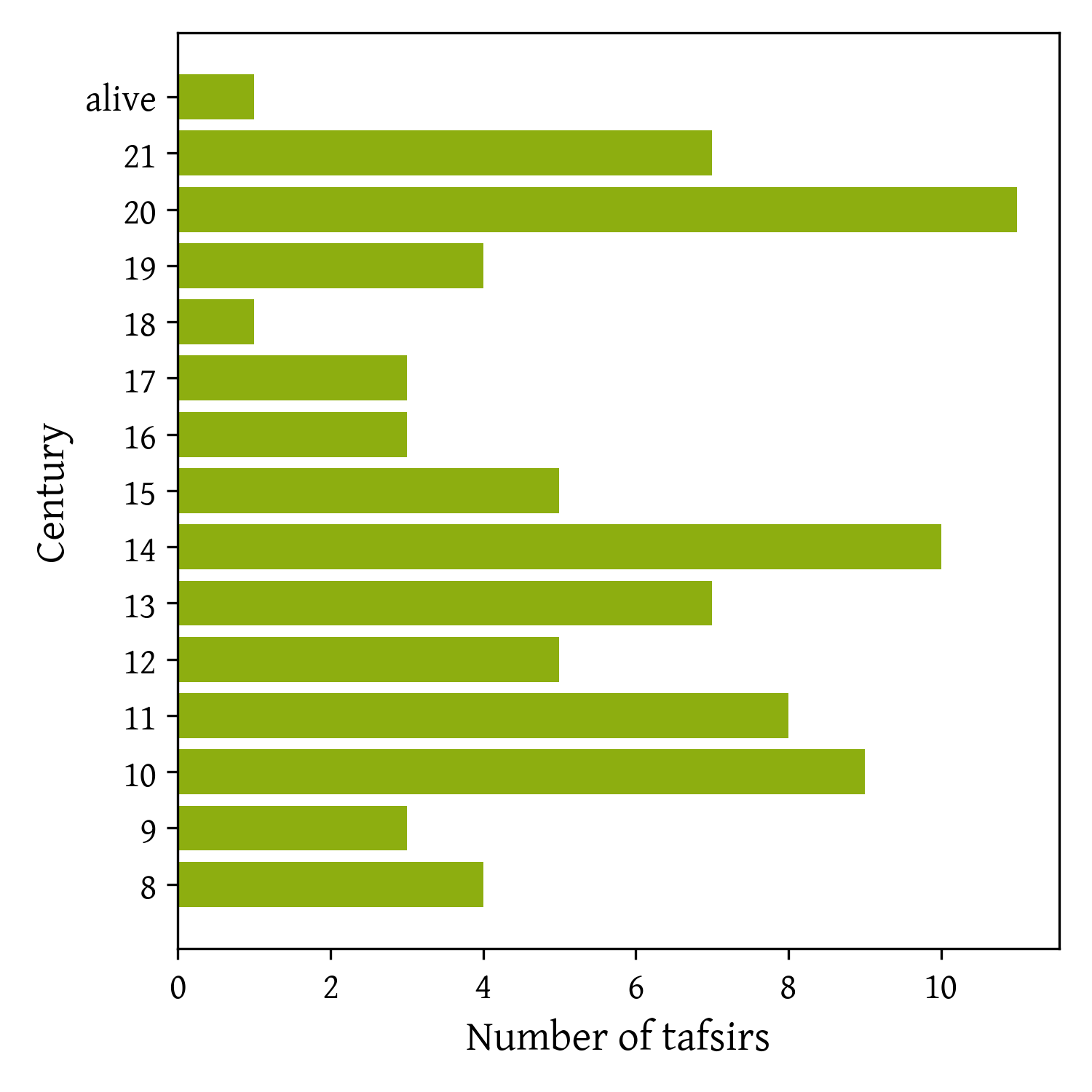

The Tafsir corpus comprises 80 Tafsir texts, the Masnavi, and the Qurʾan with a total size of approximately 72,034,114 tokens. It includes works of widely varying lengths, ranging from over 3 million tokens (al-Alusi) to about 169,000 tokens (ʿAbd al-Salam), some of which are incomplete. The corpus contains Arabic Tafsir texts dating from approximately 722 CE (based on the death dates of the authors attributed to the works, see below) up to recent times (see Figure 2). In terms of regional distribution, it primarily consists of texts from the Middle East and lacks representations from significant regions such as India and Southeast Asia.

These regional and chronological biases were already inherent in the original Altafsir.com collection, which pursued a particular political aim, namely, to “[…] adopt an ecumenical, inclusive, comprehensive, and ideologically independent approach, claiming to encompass ‘standard Classical and Modern Commentaries […] of all eight schools of jurisprudence’” (Bernhard 2024, 48). The vast number of unedited and non-digitized Tafsir texts that still exist (see Ross 2023) further underlines the limited representation of the Tafsir genre in the corpus and in the quantity of printed editions available.

In addition to the previously mentioned regional and chronological information, the Tafsir corpus also includes metadata in the following categories, which are continuously evaluated and refined:

- Theological schools

- Law schools

- Exegetical interests

It is important to note that the assignment of these metadata categories to individual Tafsir texts is carried out through their respective authors. For instance, the dating of a Tafsir text is typically determined based on the death date of its author.

In addition to these categories, the Tafsir corpus also includes annotations of Qurʾan, Hadith, and poetry quotations within the Tafsir texts. These annotations were manually created by the Altafsir team and provide an invaluable resource for advanced filtering, text retrieval (e.g., searches with or without quotations), and statistical analysis (for instance, identifying which Tafsirs contain the highest number of poetry quotations; see also Jurczyk et al. 2025 for preliminary studies in this direction).

Regarding the linguistic data, the entire corpus was processed using CAMeL Tools (Obeid et al. 2020). Although CAMeL Tools is primarily designed for Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), it enabled us to extract valuable linguistic information from the historical Arabic texts at the word level, including (de-)diacritized and stemmed forms. These outputs can be used to generate customized versions of the Tafsir data for subsequent processing, such as producing a lemmatized version of the text for semantic analysis.

The corpus is currently maintained, refined, and expanded by the A01 project, which is adding additional functionalities such as text embeddings, automated translation features, and advanced filtering and retrieval options through its internal corpus tool (see Figure 4). Both the final dataset and the web application are planned for public release at a later stage.

Bibliography

Bernhard, Adrian. 2024. Development of the Quranic WAY Metaphor in Tafsir: A Corpus Analysis Approach.

Görke, Andreas, and Johanna Pink, eds. 2014. Tafsīr and Islamic Intellectual History: Exploring the Boundaries of a Genre. Qur’anic Studies Series, edited by Institute of Ismaili Studies, vol. 12. Oxford University Press in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies.

Jurczyk, Thomas, Roman Seidel, Adrian Bernhard, Tatjana Scheffler, and Johann Buessow. 2025. “Text Mining Tafsir: Compilation and Preliminary Explorations of a Curated Corpus of 80 Qurʾanic Commentaries.” Journal of Digital Islamicate Research (Leiden, The Netherlands) 3 (1): 97–167. https://doi.org/10.1163/27732363-bja00010.

Martínez, Alicia González. 2016. “Tafsir: Quranic Commentaries Scraped and Processed.” https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kabikaj/altafsir.

Nigst, Lorenz, Maxim Romanov, Sarah Bowen Savant, Masoumeh Seydi, Peter Verkinderen, and Hamidreza Hakimi. 2023. “OpenITI: A Machine-Readable Corpus of Islamicate Texts.” Version 2023.1.8. Zenodo, October 17. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.10007820.

Obeid, Ossama, Nasser Zalmout, Salam Khalifa, et al. 2020. “CAMeL Tools: An Open Source Python Toolkit for Arabic Natural Language Processing.” Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (Marseille, France), May, 7022–32. https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/2020.lrec-1.868.

Pink, Johanna. 2010. Sunnitischer Tafsīr in der modernen islamischen Welt: Akademische Traditionen, Popularisierung und nationalstaatliche Interessen. Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/18716.

Ross, Samuel J. 2023. “What Were the Most Popular Tafsīr s in Islamic History? Part 1: An Assessment of the Manuscript Record and the State of Tafsīr Studies.” Journal of Qur’anic Studies 25 (3): 1–54. https://doi.org/10.3366/jqs.2023.0555.

Shah, Mustafa Akram Ali, and M. A. Abdel Haleem, eds. 2020. The Oxford Handbook of Qurʼanic Studies. First edition. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford University Press.

Seidel, Roman. Forthcoming. “Qur’anic Lead Metaphors and the Unfolding of their Religious Meaning: Considerations on the Theory of Metaphor and Transtextuality Applied to Qur’an and Tafsîr”. In By the Tongue of the Heart: Role and Development of Metaphors in Sufi Literature, edited by Roman Seidel and Vicky Ziegler. Special Issue of Asiatische Studien 80/2 (2026).

Seidel, Roman, and Johann Büssow. 2025a. “Mapping the ‘Straight and Solid Road’ Within the Qur’anic Landscape: Development of a Primordial Islamic Way Metaphor.” In Conceptualizing CONDUCT OF LIFE through WAY Metaphors, edited by Kianoosh Rezania, Neda Mohtashami, and Roman Seidel. Metaphor Papers 19. https://doi.org/10.46586/mp.430.507.

Seidel, Roman, and Johann Büssow. 2025b. Annotating Explicative Metaphors: An Annotation Guideline for Qur’anic Lead Metaphors and Explicative Metaphors in Exegetical Texts (Tafsir). Metaphor Papers 31. https://doi.org/10.46586/mp.451.

Sinai, Nicolai. 2009. “Fortschreibung und Auslegung: Studien zur frühen Koraninterpretation.” Diskurse der Arabistik, Band 16. Harrassowitz.